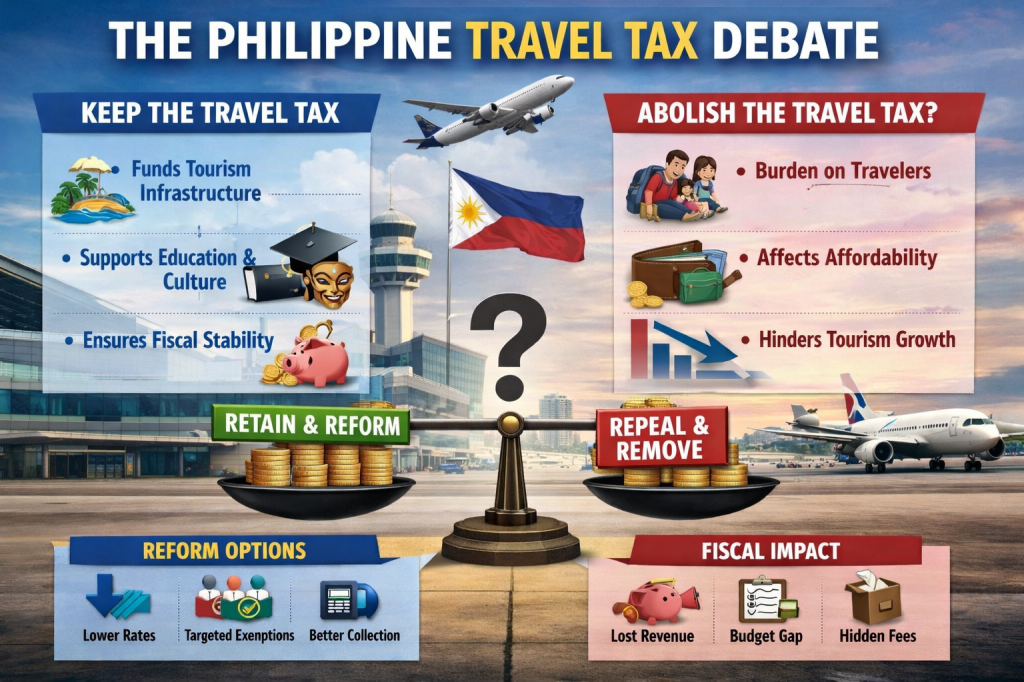

In recent years, public debate in the Philippines has intensified around the question of whether the Philippine Travel Tax should be abolished. Critics argue that the tax adds to the cost of international travel, places a disproportionate burden on low-income and first-time travelers, and contributes to price fragmentation in an already expensive travel market. Supporters, on the other hand, defend the tax as a strategic revenue instrument that funds tourism infrastructure, cultural programs, and human capital initiatives.

House Bill No. 7443, filed by House Majority Leader Sandro Marcos, proposes the abolition of the Philippine Travel Tax on the premise that it imposes an undue burden on travelers and hinders economic mobility and tourism growth. While the bill identifies legitimate concerns regarding travel affordability and regional competitiveness, the outright repeal of the travel tax is both economically and fiscally misguided. This paper argues that abolishing the travel tax would undermine dedicated funding for tourism infrastructure and related programs, shift the burden of financing to general taxation, and disrupt Philippine fiscal stability. Instead of abolition, recalibrating the tax structure and reforming its administration would better address equity and mobility concerns while preserving essential revenue streams.

This paper contends that abolishing the Travel Tax outright would undermine long-term public finance stability, remove a visible funding mechanism for critical national programs, and ultimately shift burden to the general body of taxpayers. Rather than repeal, what is needed is meaningful reform—rate rationalization, equity-based exemptions, administrative modernization, and stronger transparency and accountability frameworks.

The Philippine Travel Tax finds its legal foundation in Presidential Decree No. 1183 (1977), also known as the Travel Tax Code of 1977. The original rationale was to generate revenue dedicated to tourism and related development activities, a reflection of the then emerging global recognition of tourism as both an economic driver and a public good (Tourism Infrastructure and Enterprise Zone Authority [TIEZA], n.d.). The Travel Tax thus originated not as an arbitrary departure charge but as an instrument aligned with a broader policy objective: to ensure that Filipino travelers contribute toward the preservation and expansion of national tourism assets, cultural heritage programs, and educational development funds that benefit the wider society.

Tourism policy literature supports the idea that user-linked levies can have justifiable place in a diversified tax system. Public finance scholars have long differentiated between general taxes and user fees, emphasizing that when individuals benefit from specific government services or infrastructure, a direct charge linked to usage can offer both fairness and accountability (Musgrave & Musgrave, 1989; Bird & Slack, 2007). In this sense, the Travel Tax functions like a user fee: it targets a group of service beneficiaries—international travelers—and allocates the proceeds to programs from which they and the broader tourism ecosystem benefit.

Advocates of abolishing the Travel Tax typically ground their arguments in three key points: affordability, equity, and administrative efficiency. The affordability argument suggests that each mandatory fee imposed on travelers ultimately raises the total cost of travel and could serve as a barrier to mobility for middle- and low-income families, students, overseas workers, and micro-entrepreneurs (Smith, 2021). From this perspective, a Travel Tax—however modest—is an additional cost that combined with airfare, fuel surcharges, airport fees, and other travel-related taxes, compounds the financial burden and potentially dampens travel demand.

The equity critique contends that a flat or near-flat Travel Tax, applied uniformly to all passengers regardless of income or fare class, can be regressive. In the simplest terms, a traveler with limited financial resources pays a similar amount to one with significantly higher means, thus allocating a disproportionate share of travel cost to the less affluent (Aronsson & Fors, 2003). Lastly, administrative friction is often cited: if travelers experience confusion about exemptions, where and when to pay the tax, or how to qualify for reduced rates, the Travel Tax may create unnecessary hassle at airports or ticketing counters.

While these arguments are grounded in valid concerns about cost and equity, none of them, when examined rigorously, support the policy choice of complete repeal. Instead, they point toward the need for structural reform that addresses the real constraints of fairness and administration while preserving the underlying fiscal and developmental purpose of the tax.

The fiscal significance of the Travel Tax cannot be dismissed lightly. In a country where tourism development has become an increasingly important sector for economic growth, foreign exchange earnings, infrastructure investment, and employment generation, dedicated revenue streams are valuable. Travel Tax revenues contribute to the operations of the Tourism Infrastructure and Enterprise Zone Authority (TIEZA), which is responsible for tourism infrastructure, enterprise zone development, and destination competitiveness projects. Additionally, under broader policy frameworks influenced by the Tourism Act of 2009, portions of Travel Tax collections have been associated with funding human capital development, especially in higher education, and with supporting cultural programs through agencies like the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (Presidential Communications Office, 2023).

Critically, this revenue is not fungible in the way most general tax revenues are. It is earmarked—in policy if not always in practice—for specific purposes. While economists often caution against rigid earmarking due to potential inflexibility in budget allocation (Rosen & Gayer, 2014), there is a countervailing argument that dedicated funds improve planning and accountability for projects with long horizons and multi-year financing needs. Tourism infrastructure projects, such as access roads, visitor facilities, safety measures, and digital destination platforms, require stable, predictable funding that cannot be assured through annual appropriations alone.

Moreover, as Bird and Slack (2007) observe in international contexts, revenue earmarked for local or sectoral investment can provide municipalities and sector authorities with the confidence to plan capacity expansions and quality enhancements. The Travel Tax’s presence within the Philippine fiscal system thus plays a dual role: it provides revenue for current programs and sends a long-term signal about the government’s commitment to tourism as an engine of growth.

If the Travel Tax were abolished, the government would face immediate fiscal questions. The first is the budget gap created by the elimination of a designated revenue stream. The government could choose to replace this revenue through general taxation—raising income, value-added, or corporate taxes—or through borrowing. Either option spreads the cost among the broader taxpayer base, including those who do not travel or use tourism infrastructure, raising questions of horizontal equity.

A second risk is the likelihood of replacement charges emerging through administrative or quasi-administrative means. Airport operators, carriers, or local authorities might introduce alternative surcharges to recoup lost revenue or fund needed services. Such charges, levied outside the legislative tax framework, may not be subject to the same degree of public scrutiny, accountability, or policy coherence that a statutory tax enjoys.

Finally, abolishing the Travel Tax weakens the benefit-linkage principle. When travelers are directly tied to a specific contribution that funds aspects of tourism development, they have a palpable stake in the quality and sustainability of the sector. Removing this linkage risks blurring both fiscal transparency and policy purpose.

In contrast, there are multiple policy alternatives that can retain the Travel Tax’s revenue and developmental role while responding substantively to concerns about fairness and cost. These alternatives include:

- Tiered or Progressive Tax Rates. Rather than a single flat rate, the Travel Tax could be structured into tiers based on class of service, fare category, or destination zone. Such tiering would embed ability-to-pay considerations into the levy without dismantling it.

- Expanded Exemptions and Targeted Relief. Exemptions can be expanded for categories such as students on academic programs, medically necessary travel, humanitarian travel, and low-income migrant-worker families under clear criteria.

- Modernized Collection Mechanisms. Integrating the Travel Tax into ticketing systems or e-travel platforms reduces administrative friction and confusion, making the levy more predictable and less intrusive at point of departure.

- Enhanced Transparency and Accountability. Mandating regular public reporting on Travel Tax revenues, disbursements, and project outcomes can strengthen public trust and demonstrate concrete returns on the levy.

Addressing equity concerns, especially around regressivity, requires thoughtful design. A flat or uniform charge treats all travelers alike, but it does not differentiate by income or means. A progressive tiered structure better approximates ability to pay, aligning with normative principles in public finance that advocate for tax structures that support equity without stifling mobility (Atkinson & Stiglitz, 1980).

Efficiency concerns—particularly around compliance costs and administrative bottlenecks—are best handled through process reform. As global best practices indicate, embedding travel-related levies into digital ticketing or departure procedures reduces transaction costs for both government and travelers (OECD, 2018). Countries that have reformed departure taxes often emphasize modernization and simplification rather than elimination.

The debate over the Philippine Travel Tax encapsulates deeper questions about public finance, equity, competitiveness, and national development priorities. While legitimate concerns have been raised about the cost burden on travelers and the need for equitable treatment, abolition of the Travel Tax is not the most effective policy solution. Such a move would weaken a dedicated funding stream for tourism and related programs and would impose hidden costs through general taxation or new administrative charges.

House Bill No. 7443’s proposal to abolish the travel tax appeals to public sentiment on travel affordability and mobility; it also highlights regional integration concerns. However, outright elimination of the travel tax is neither fiscally sound nor necessary for achieving the bill’s underlying objectives. The travel tax plays a critical role in financing tourism infrastructure and culture and aligns with foundational principles of equitable, user-linked public finance.

The better path for Congress is to pursue a comprehensive reform agenda that preserves the Travel Tax’s fiscal role while addressing equity concerns and administrative inefficiencies. Progressive rate design, targeted exemptions, collection modernization, and transparent reporting can transform the Travel Tax from a politically controversial levy to a model of inclusive and accountable tax policy. Fiscal stability, sectoral development, and social fairness are not mutually exclusive objectives. With thoughtful reform rather than abolition, the Philippine Travel Tax can continue to support the nation’s tourism sector, enhance public investment outcomes, and ensure that international travel remains both sustainable and equitable.

References